Water Pollution : Everyday Sources and Solutions

A simple overview of wastewater pollution, it's impact, and how it can be mitigated at home

Often taken for granted, water is a vital yet rapidly dwindling resource.

Safe drinking water and proper sanitation are not only essential to human health in a direct sense, but water also represents an indispensable part of the ecosystems that all living beings on this earth rely on. Floods, droughts, wildfires, rising sea levels; the crucial role of water in our planet’s equilibrium has been felt in some of the most devastating manifestations of climate change.

However, there are many ways in which the management of water can either contribute to or offset the toxic impacts of rapid urban expansion and industrialization.

Though not all best practices will be universally feasible, each small change adopted marks a significant step towards more progressive norms, increased availability of more sustainable products, and widespread policy reform.

Click here to see an infographic detailing 200 ways to save water at home

There are a multitude of factors that impact wastewater, creating a cascade of environmental consequences. Following are a few of those concerns and what can be done on an individual level to protect Earth’s keystone resource.

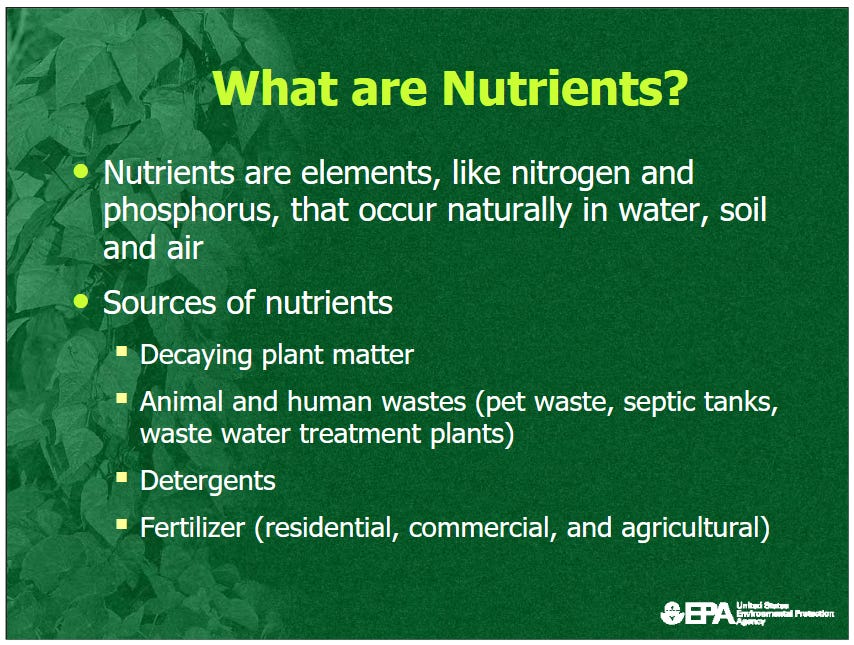

Nutrient pollution

Nutrients, as their name might imply, serve as food for plants. While these can promote growth and productivity when applied at appropriate rates, the fertilizers used on lawns and gardens pose a significant source of pollution to waterways.

Nitrogen and phosphorus disrupt healthy aquatic ecosystems by causing overgrowth of aquatic plants and algae through a process called eutrophication (EPA, 2024c). Aside from contributing to the creation of toxic algae blooms, these conditions eventually kill off aquatic life as the overgrowth exhausts the water’s available oxygen (EPA, 2024c; Zhang, 2017).

Once nutrient pollution has occurred, it is extremely difficult to reverse the ecological destruction — even after the source has been eliminated (Zhang, 2017).

In order to avoid over-application of nutrient-rich fertilizers, the most accurate method of soil testing is sending away to a laboratory that processes soil samples. DIY soil testing kits are also available at many garden centres. Though they cannot provide the same level of accuracy as lab testing, they may still help to inform conservative fertilizer use in conjunction with consideration to plant-specific needs.

Other household sources also contribute to nutrient pollution, including household products — such as detergents containing phosphates, and pet waste that isn’t cleaned up.

Click here for more information on what can be done at home to reduce nutrient pollution

Runoff

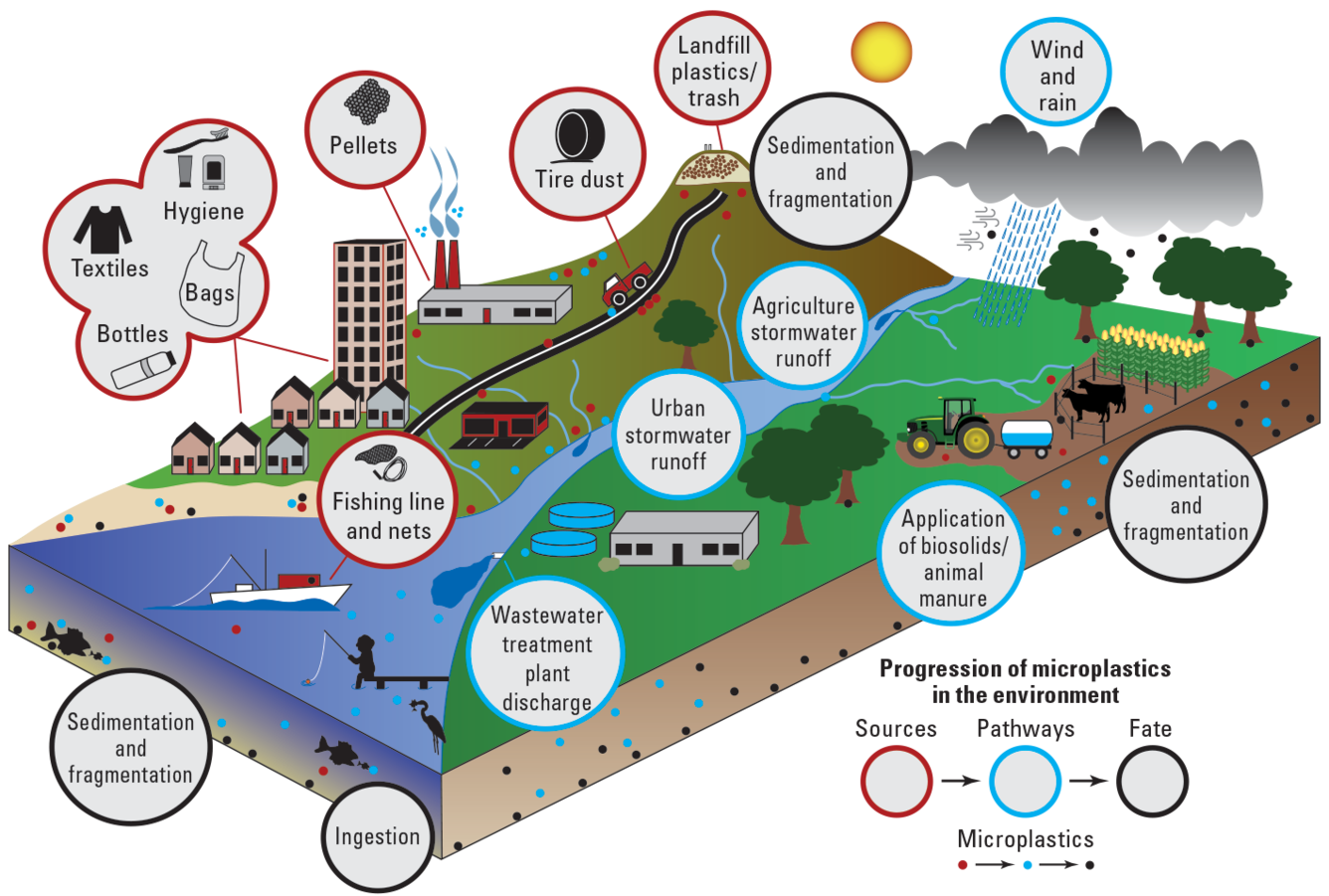

Surface runoff serves as a another major source of water pollution. When more water is introduced to the environment than the earth can absorb, such as after heavy rain or snow melt, it runs over the land and into natural bodies of water. Along its journey, it collects various contaminants (including nutrients, chemicals, and microplastics) and deposits them in water sources.

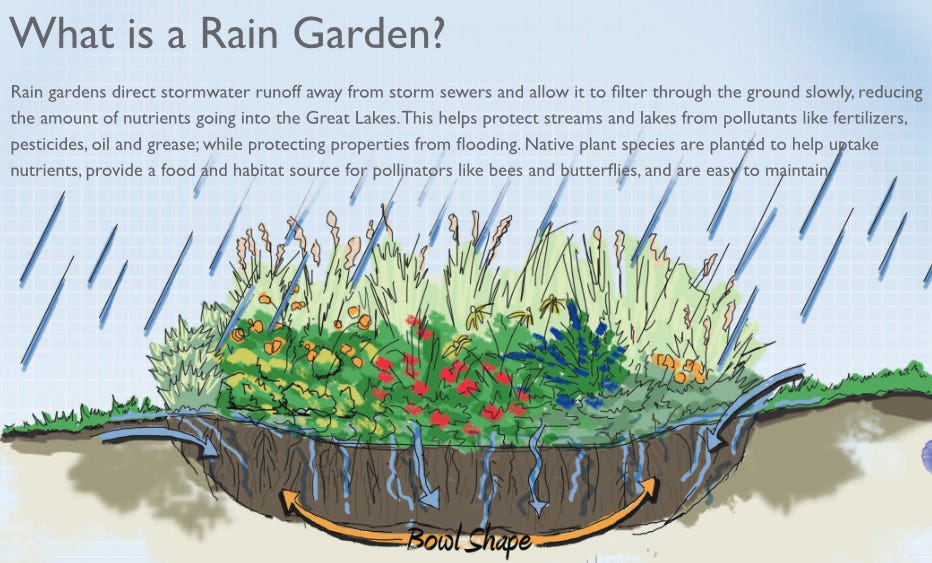

One way to mitigate runoff risk is to consider creating a rain garden. Water can be directed to collect in a shallow, depressed area of the yard housing a garden of native plant species with deep root systems. Excess nutrients and other pollutants can then instead be filtered through the vegetation and soil (Obropta et al., 2006).

Vegetative filter strips or buffers are most commonly used in agriculture, but similarly help protect bodies of water from contamination (Health Canada, 2024).

Native plants are not only adapted to region-specific conditions, but also enhance biodiversity through providing resources for wildlife threatened by urban and agricultural expansion.

For more information on the important role of native plants:

Another way to reduce run-off (while perhaps also reducing the water bill) is to set eavestroughs up to drain into a rain barrel that can be used to water gardens.

Click here for more information and resources related to reducing runoff at home

Medical waste

Pharmaceuticals may contaminate water systems if they are washed down the drain, or can pollute groundwater if they are sent to landfills and allowed to seep into the earth. Many medications have been detected in both urban and rural water systems, which have been linked to behavioural and physical changes, organ damage, genotoxicity, and mortality in aquatic animals (Anand et al, 2022; Kusturica et al., 2022). Antibiotic pollution also poses a serious threat to ecosystems and may contribute significantly to the spread of antibiotic-resistant genes through groundwater (Zainab et al., 2020).

Though different regions have different programs available, drug take-back initiatives for safe disposal of unwanted medications are in place across various communities, governments, and organizations.

Collection programs also exist for farm pharmaceuticals that may not be accepted by standard drug collection programs (Unwanted Pesticides & Old Livestock/Equine Medications, 2024).

Antibiotic resistance and pollution is often thought of in relation to medications, but studies have found that antibacterial additives in soap can sabotage water treatment processes that rely on microorganisms (amongst other threats to ecosystems) while not even cleaning more effectively than regular soap (Chirani et al., 2021).

Microplastics

Little plastic exfoliating beads were once ubiquitous in soaps and facial cleansers. Approximately a decade ago, many companies began to phase them out as governments began the process of regulating them on account of the environmental damage they were causing (Landau, 2013; Government of Canada, 2023). However, microplastics and other polymers are still common ingredients in the personal care and beauty industry (Cubas et al., 2022; Khare & Khare, 2022).

Microplastics pose an insidious risk in their ability to attract, concentrate, and distribute other harmful contaminants — including antibiotics, antibiotic-resistant genes, persistent organic pollutants, chemicals, and heavy metals (Liu et al., 2022).

Because they do not readily break down, plastics accumulate at an exponential rate in soil and water. They can also be small enough to be transported through the atmosphere over long distances (Wu et al., 2016; Zhang et al, 2019; Liu et al., 2022)

Beat the Microbead provides a list of ‘Red Flag’ ingredients as a reference to help consumers identify microplastic ingredients in personal care products.

Common plastic ingredients include but aren’t limited to:

Polyethylene (PE) Polyethylene terephthalate (PET)

Nylon (PA)

Polypropylene (PP)

Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)

Polyester fibres shed from clothing during laundry make up another major source of microplastic pollution. (Tian et al., 2020; Okamoto, 2021)

Some governments have already enacted legislation that mandates all new washing machines be equipped with microplastic fibre filters. For those with older machines, however, there are a number of filter options available. One study of microfibre laundry filters (Napper et al., 2020) found the XFiltra filter and the Guppyfriend laundry bag to significantly reduce the amount of fibres shed into wastewater.

PlanetCare, another filter producer, provides a recycling service for its used filters. According to Riya Anne Polcastro’s reporting for Triple Pundit (2023), the company’s pilot program has used the recycled material to produce insulation mats and mesh for chairs.

The comparative efficacy (and ease of use) of different filter designs has varied somewhat across several recent studies, but results have shown promise in the reduction of microplastics in wastewater (Erdle et al., 2021; Abourich et al., 2024; Kim et al., 2024).

Final notes

Although this overview is by no means exhaustive, it introduces some key concepts that may warrant further exploration.

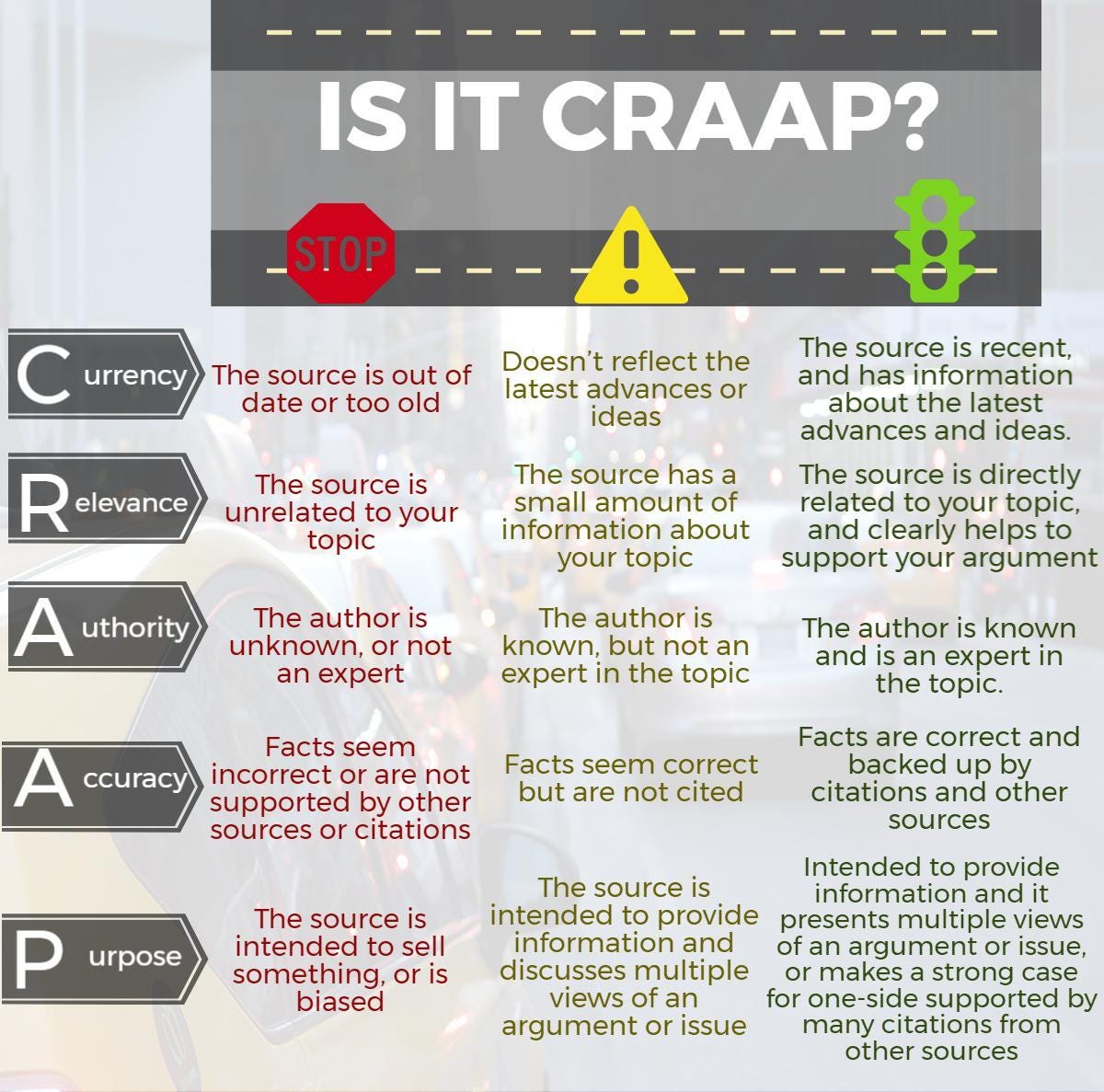

University extension websites are generally accessible sources of reputable, science-backed information. If peer-reviewed journals cannot be accessed, respected journalistic sources will also often summarize study results; interviewing researchers and presenting findings in a comprehensible format. Various government departments may have valuable information available to the general public as well.

All sources, even peer-reviewed studies vary in quality. In an age of disinformation and misinformation, it is increasingly important to be cognisant of bias.

Click here for more information on evaluating sources

Armed with knowledge and understanding, each person holds the power to enact cumulative change for brighter future, and, perhaps more importantly, to make a positive difference for the humans and animals of today.

References

Abourich, M., Bellamy, A., Ajji, A., & Claveau-Mallet, D. (2024). Washing machine filters to mitigate microplastics release: Citizen science study to estimate microfibers capture potential and assess their social acceptability. Environmental Challenges, 16, 100984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2024.100984

Anand, U., Adelodun, B., Cabreros, C., Kumar, P., Suresh, S., Dey, A., Ballesteros, F., & Bontempi, E. (2022). Occurrence, transformation, bioaccumulation, risk and analysis of pharmaceutical and personal care products from wastewater: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 20(6), 3883–3904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-022-01498-7

Beat the Microbead. (2022). Guide to microplastics - Check your products. https://www.beatthemicrobead.org/guide-to-microplastics/

Catherine Zimmerman (TheMeadowProject). (2011, July 18). Doug_Tallamy_wcredits.mp4 [Video]. YouTube.

City of Windsor. (n.d.). Rain Gardens. https://www.citywindsor.ca/residents/environment/climate-change-adaptation/climate-resilient-home/rain-gardens

Connect4Climate. (n.d.). 200+ ways to save water. https://www.connect4climate.org/infographics/200-ways-save-water

Corbett, J. L. (2023, December). Microplastics Sources, Pathways and Fate Conceptual Diagram. USGS. https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/microplastics-sources-pathways-and-fate-conceptual-diagram

Cubas, A. L. V., Bianchet, R. T., Reis, I. M. a. S. D., & Gouveia, I. C. (2022). Plastics and Microplastic in the Cosmetic Industry: Aggregating Sustainable Actions Aimed at Alignment and Interaction with UN Sustainable Development Goals. Polymers, 14(21), 4576. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14214576

CWC. (2024, November 14). Evaluating Sources: CRAAP. Central Wyoming College Library. https://libguides.cwc.edu/bias

EPA. (2008, June). Sowing the seeds for healthy waterways: How your gardening choices can have a positive impact in your watershed [Slide show presentation]. EPA-820-C-08-001. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/documents/gardenbasicnotes.pdf

EPA. (2011). How to dispose of medicines properly. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/P100ZW8A.PDF?Dockey=P100ZW8A.PDF

EPA. (2024a, February 29). Ammonia. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/caddis/ammonia

EPA. (2024b, May 23). What you can do to soak up the rain. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/soakuptherain/what-you-can-do-soak-rain

EPA. (2024c, November 15). The problem. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/problem

EPA. (2024d, November 18). What you can do: in your home. United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/what-you-can-do-your-home

Erdle, L. M., Parto, D. N., Sweetnam, D., & Rochman, C. M. (2021). Washing machine filters reduce microfiber emissions: evidence from a Community-Scale pilot in Parry Sound, Ontario. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.777865

Government of Canada. (2017, July 31). Wastewater management. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/wastewater/management.html

Government of Connecticut. (2016). Microbeads. Connecticut’s Official State Website. https://portal.ct.gov/deep/municipal-wastewater/microbeads

Health Canada. (2024, April 8). Vegetative Filter Strips Factsheet. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/consumer-product-safety/pesticides-pest-management/growers-commercial-users/runoff-mitigation/vegetative-filter-strips.html

HPSA & College of Pharmacists of Manitoba. (n.d.). Manitoba Medications Return Program FAQs and Operational Tips. College of Pharmacists of Manitoba. https://cphm.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Manitoba-Medication-Return-Program-FAQNov2014.pdf

Khare, R., & Khare, S. (2022). Polymer and its effect on environment. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society, 100(1), 100821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jics.2022.100821

Kim, S., Hyeon, Y., Rho, H., & Park, C. (2024). Ceramic membranes as a potential high-performance alternative to microplastic filters for household washing machines. Separation and Purification Technology, 344, 127278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2024.127278

Kusturica, M. P., Jevtic, M., & Ristovski, J. T. (2022). Minimizing the environmental impact of unused pharmaceuticals: Review focused on prevention. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1077974

Liu, P., Dai, J., Huang, K., Yang, Z., Zhang, Z., & Guo, X. (2022). Sources of micro(nano)plastics and interaction with co-existing pollutants in wastewater treatment plants. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 53(7), 865–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2022.2095844

Maloney, A. (2024, February 7). Media Bias Handout. OER Commons. https://oercommons.org/authoring/54677-media-bias-handout/view

Nowlain, L. (2020, April 25). Give information the CRAAP test. ALSC Blog. https://www.alsc.ala.org/blog/2020/04/information-literacy-for-parents/craap/

Obropta, C., Sciarappa, W., & Quinn, V. (2006). Rain gardens. Rutgers Cooperative Research & Extension. https://esc.rutgers.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/RAIN-GARDENK.pdf

Okamoto, K. (2021). Your laundry sheds harmful microfibers. Here’s what you can do about it. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/wirecutter/blog/reduce-laundry-microfiber-pollution/

Polcastro, R. A. (2023, November 7). The push to upgrade the world’s washing machines and keep microplastics out of the ocean. Triple Pundit. https://www.triplepundit.com/story/2023/washing-machine-filter-microplastics/787671

Randall, D., & Tsui, T. (2002). Ammonia toxicity in fish. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 45(1–12), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00227-8

Tian, Y., Chen, Z., Zhang, J., Wang, Z., Zhu, Y., Wang, P., Zhang, T., Pu, J., Sun, H., & Wang, L. (2020). An innovative evaluation method based on polymer mass detection to evaluate the contribution of microfibers from laundry process to municipal wastewater. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 407, 124861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124861

Unwanted pesticides & old livestock/equine medications. (2024). Cleanfarms. https://cleanfarms.ca/materials/unwanted-pesticides-animal-meds/#toggle-id-1

Wu, W., Yang, J., & Criddle, C. S. (2016). Microplastics pollution and reduction strategies. Frontiers of Environmental Science & Engineering, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11783-017-0897-7

Zainab, S. M., Junaid, M., Xu, N., & Malik, R. N. (2020). Antibiotics and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) in groundwater: A global review on dissemination, sources, interactions, environmental and human health risks. Water Research, 187, 116455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116455

Zhang, H. (2017, April). Phosphorus and water quality. Id:PSS-2917 Oklahoma State University Extension https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/phosphorus-and-water-quality.html

Zhang, Y., Gao, T., Kang, S., & Sillanpää, M. (2019). Importance of atmospheric transport for microplastics deposited in remote areas. Environmental Pollution, 254, 112953. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.121